One hundred years ago, Alvis built this car in a quest for competition success to publicise its brilliant new overhead-valve engine. They called it Racing Car No 1 – does it live up to that name today?

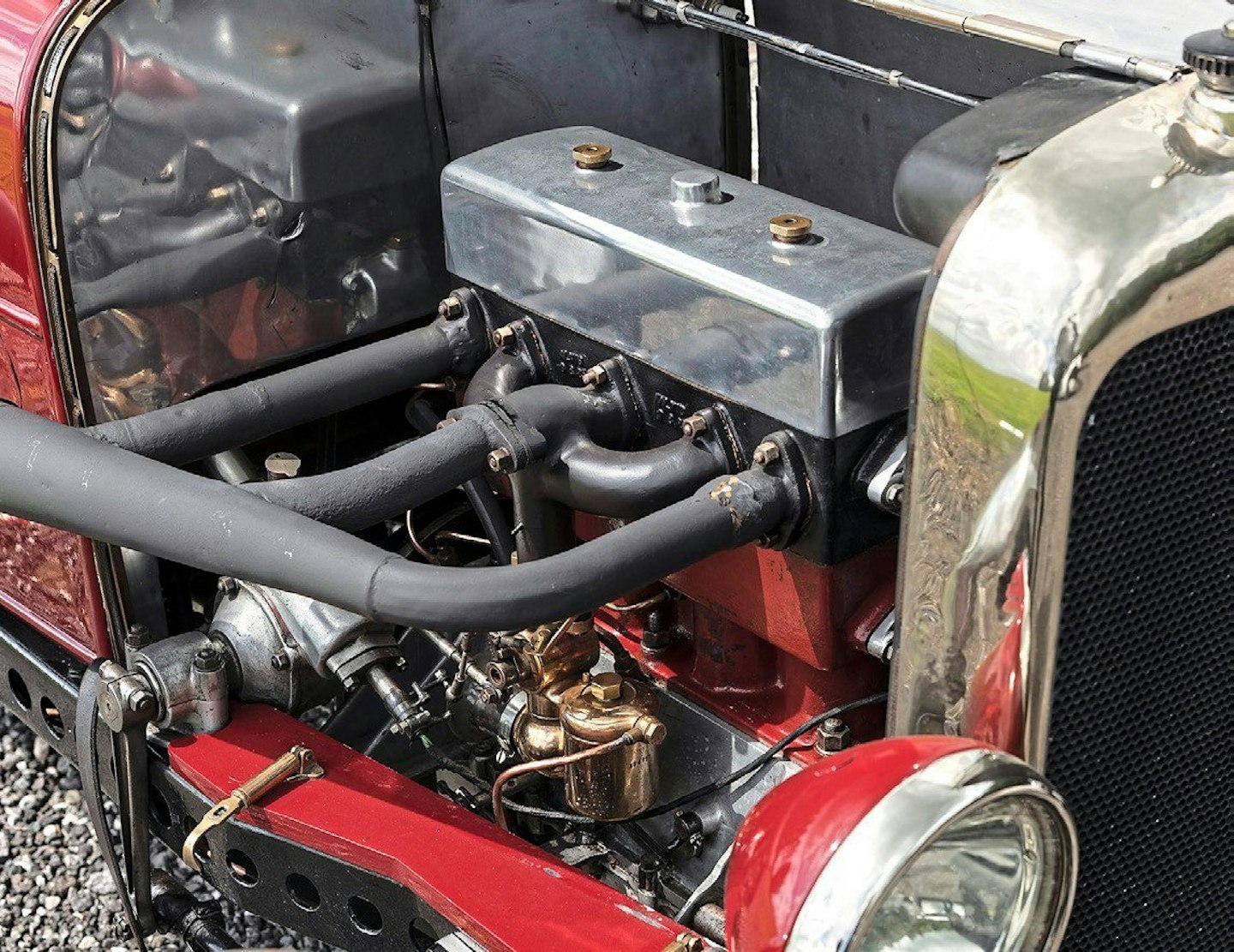

After a century of existence, this car has many tales to tell. It was completed in June 1923, built from a much-drilled Alvis 10/30 chassis of 1921 and a 10/30 crankcase, upgraded by the addition of the brand new 12/50 cylinder block and overhead-valve cylinder head. It was designated by Alvis as 12/50 Racing Car No 1 and was built for sprint and hill climb competition. In the hands of Alvis works driver Major Maurice Harvey, it began winning straight away. But that covers only the first six months of its history.

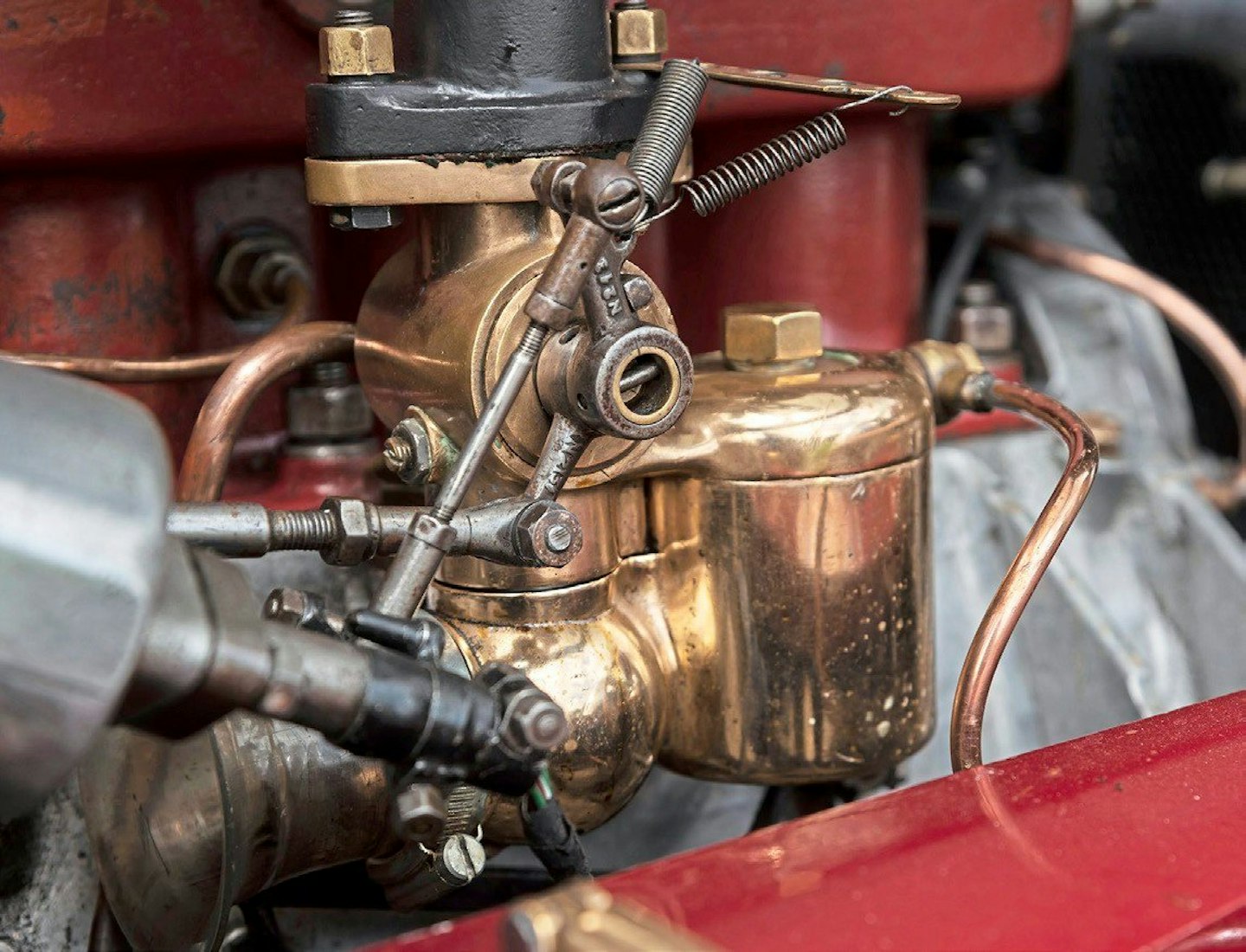

We’ll get into the other 99.5 years after a spell behind the wheel. I’m at Tom Hardman’s showroom on a farm in rural Lancashire, not a bad place to learn how to drive a racing car created before front-wheel brakes were regarded as necessary. Soon I’ll venture out in public, but first – the starting procedure, which is rather involved. There are taps and pipes everywhere. A pump, too, like something you might use to pressurise an insect-sprayer. There is also a nickelplated ignition switch I recognise from my own 1923 Alvis, marked OFF and ON, with a pointer resembling a tiny Bakelite sausage you can turn from one to the other.

It goes like this. Turn on the fuel taps. Pump some air pressure into the fuel tank with the plunger on the outside left of the cockpit, until the gauge shows anything other than zero. Reach through the hand-hole in the offside bonnet panel and tickle the carburettor on the float chamber to flood it. Then, with the ignition off, use the starting handle to turn the engine over a few times to draw in some mixture. Retard the ignition with the timing control lever and turn the switch to ‘ON’. Ask Tom Hardman to apply the choke, which is nothing more than a special piece of flat metal on a keyring in Tom’s pocket that he presses to the mouth of the carburettor. Move the starting handle down slowly and find some resistance. Then give a swift pull upwards – never try to start on a down-stroke, for fear of a violent kickback – and it should burst into life.

‘A racing car created before front brakes were seen as necessary’

To my astonishment, it works first time from stone cold. Tom has clearly learned the drill very well and passed it on exactly. Racing Car No 1 settles into a pocketa-pock idle and sits there, trembling lightly and scenting the air with Castrol R. So far, so docile – and, as hundred year-old racing cars go, something of a pussycat. Will it be quite so obliging to drive?

Thanks to the cut-down cockpit side, your right knee can splay out as you hunker down behind the aero screen. The biggest worry is moving your right foot from the central accelerator and passing it under the steering column to the brake pedal on the right. Then there’s the gearlever, waiting outside the cockpit to produce a cringe-inducing crunch when engaging gear from a standstill. This car has no clutch stop, and the cone clutch assembly would normally be well enough lubricated to slow down and stop spinning the gearbox input shaft soon after you dip the pedal, but this one has seen little use since before Covid. Still, if you set a slow idle, and take some speed off the whirling metal by half-engaging second gear for a moment or two, you can click it smartly into first. Clutch pedal up and away you go.

Now it gets easier. The flywheel is quite light and the gearbox ratios seem more evenly spaced than other vintage Alvis gearboxes, so you double-declutch smartly into second, build speed, tap-dance smartly again into third and then again for top. Which isn’t worth bothering with below about 40mph, because the tall back axle ratio needs revs on the clock to allow the engine to pull cleanly. The rear axle ratio is high and the light flywheel combines with Racing Car No 1’s relative lack of torque (it sacrifices low-revving grunt for a very high redline, up near 5000rpm) to make it less than happy in slow traffic… as I soon discover when I venture out, managing to stall the engine at a junction in the village. Cue red-faced acrobatics as I leap forth and repeat the starting palaver.

‘It won speed trials, and was sometimes competing twice or three times in a week’

I had expected No 1 to be geared lower for hill climbing. The rear axle ratio feels rather tall, which means midrange acceleration is stronger than it is off the line. The centre of gravity feels a long way up, so the high-ratio steering (pleasingly light and direct) needs a careful touch if you’re not to unbalance the car during sudden changes of direction. There are rod-actuated brakes on the rear wheels only, but equally large handbrake shoes alongside them in the same drums. Using the latter (or a bit of both) scrubs off some speed. But not much. Mind you, if they were more powerful you could lock the two skinny tyres very easily with so little weight over the back of the car.

In its era No 1 must have been formidable, because only a week after completion it was making Fastest Time of the Day. The hill climbs at which it triumphed are now almost forgotten: South Harting, Sharnden, Ringinglow, Peak Hill. Kop Hill has made a comeback as a classic event. The Alvis won speed trials, too – in Southsea and Thetford – and was sometimes competing twice or three times in a week.

Two other 12/50 racers followed No 1, completed by early September 1923 to much the same specifications, but with streamlined Brooklands bodies. They were immediately entered for the track’s major event that year - the 200 Miles Race, held at season’s end in October. This success has become a part of Alvis legend, because it did much to make the company’s name – though knowing that it came on the back of a highly successful summer on the hills for Number 1, and that the factory would have learned lessons from how No 1’s engine was behaving, helps put the win in context. Major Harvey took one of the two new racers and defeated rapid but less reliable opposition, including Malcolm Campbell in a twin overheadcam supercharged Fiat. Harvey and riding mechanic George Tattersall won at an average 93.29mph, a new class record.

The Autocar offered glowing praise. ‘The sharp bark of its smooth engine never missed a beat, nor faltered, nor altered its pitch. It ran as Alvises run in everyday use – sturdy, swift and steady.’ It also averaged a remarkable 24mpg, humming along at 4000rpm. Clearly it had the makings of an impressive road car. Alvis’s Managing Director, TG John, didn’t think it got sufficient press attention at the time. By 1929, though, he said, ‘There is no doubt that without competitions and racing, it would have taken us another ten years to get as far as we have now.’

They had indeed got a long way. By 1929, Alvis had sold almost 3000 12/50s and it had secured a reputation as a quick, sturdy and well-engineered machine – something the model would never lose. The success of the 12/50 funded the innovative (though loss-making) Front Wheel Drive and the six-cylinder Silver Eagle that led eventually to the Speed 20. Racing Car No 1 represents the foundation on which that success was built.

You can feel it in every hill and sweeping corner. Partly this is thanks to No 1’s low weight, which reveals everything in greater detail, but it’s mainly down to the crackling overhead-valve engine. I find myself wondering whether to overtake a dawdling hatchback with a blip down into third, then I remember what I’m driving... and those brakes. You wouldn’t even consider such a move in any other four-cylinder, 1.5-litre car from 100 years ago. A ‘bullnose’ Morris Cowley, a typical side-valve example of the 12hp class, makes 40mph feel like plenty. This car will do twice that and more – and even in roadgoing tune, a 12/50 SA could pass 70mph. You’d need a Bentley 3 Litre to keep up, and in 1923 they cost £1000 for a rolling chassis, sans coachwork. A 12/50 SA Sports was £550, all in.

So what happened to No 1 after the limelight faded?