The 212 Export was designed for gentleman racers, and its success helped forge the Ferrari racing legend; in this car’s case, on the Mille Miglia and the Targa Florio

The great road races of the first half of the 20th century hold a very special place in the affections of motor racing fans; epic in their proportions and feats of daring, romantic in their embodiment of spirit and passion. The cars that took part in them are hallowed objects to the faithful, icons of a lost era of bravery and innocence.

Climbing carefully into the cockpit of Ferrari chassis number 0158 ED, a 212 Export, and sliding down into the seat – those big steering wheels always get in your way – the spell immediately begins to overtake me.

Maybe it’s the pared-down sparseness of the cockpit – nothing you don’t need – or maybe it’s just knowing what this car did. 0158 ED is still a very original car, no sugar-coating American restorer has managed to lacquer the life out of it. Its transmission tunnel and bulkhead sport the odd ding and dint, but the panels (apart from a straightening of one rear haunch) are as they came off the bucks at Touring in 1952. Such diminutive, delicate lines for a hard-fighting street racer. Look at those curves that cup the front and rear lights, the folded line that runs the length of the body. Barchetta; little boat. But don’t get carried away with the cuteness, pressing the starter button tells a different story.

I turn the key and the fuel pump begins a croaking tick-tick, drop my thumb to the dim red light glowing in the centre of the dash… and press. The sound is like a heavy metal disc spinning on a granite slab and as the cylinders fire through the block, the starter motor signs off with a faint boxing bout bell chime. The engine coughs, sighs and chatters. Round one.

There have been many round ones in this racer’s life. Ferrari brought out the 212 Export, a direct descendant of the 166MM launched in 1951. As the name Export suggested, the model was aimed at taking the new, upstart manufacturer’s name out into the competition world. Here was a very capable, upmarket club(ish) racer that could be bought off the shelf, ready to go.

0158 ED was snapped up by Baron Luigi Bordonaro di Chiaramonte, a Sicilian aristocrat whose father had been one of Vincenzo Florio’s inner cabal and one of the keen supporters of a new race, the Targa Florio, back in 1906. Bordonaro already had experience of the Targa Florio having driven (and crashed) in the 1951 race in a 166MM. He would have also seen Franco Cornacchia and Giovanni Bracco achieve second place in a 212 Export, behind Franco Cortese in a Frazer-Nash/BMW Le Mans 2.0-litre. Not only that, an Export would win the Giro di Sicilia that year and a 212 Inter the gruelling Carrera Panamericana.

By February ’52 Bordonaro had his own 212 – the last of only seven Export Barchettas built by Touring. By April he was competing with it in the Giro di Sicilia and the Palermo-Monte Pellegrino, where he finished first overall. By now, he would certainly have enough of a feel of the car for the Targa in June.

Wriggling to find a comfortable position, I’m wondering if this is the kind of place I’d want to experience the eight 44-mile laps of the great race. Sicily’s most celebrated event was in essence a circuit race using the twisting, patchy mountain roads of the Madonie as its track – with the odd village and a bit of volcanic subsidence thrown in. All that can wear a driver out pretty quickly.

Although the car is low, I sit quite upright, more so than in an AC Ace or Austin Healey of a similar era. The big steering wheel is the length of my forearm away, filling my lap and almost brushing the tops of my knees. The large white-numbered tacho is clearly visible behind, the speedo off somewhere to the left.

From the off, the 212 is responsive, the V12 immediately answering its throttle while pulling away without any drama. The steering is firm and positive. Even straight ahead, it seems like where I point it, it will go. But from the position of the wheel, I think a lot of strain is going to fall across my elbows, upper arms and chest. As I turn into a low-speed bend, I’m thinking there doesn’t seem to be a lot of that ‘as the speed builds, it gets lighter’ aspect to the handling. A few sessions on a rowing machine might not be a bad idea before tackling a big event in this little barchetta.

Go too hard into a bend and the steering and balance fights me, the nose pushing out into stubborn understeer. I find I’m holding it firmly on the turn, locked wrists and taut shoulders, gradually easing up as I press the throttle on the exit. There’s certainly no shortage of shove. Coming out of the turn, the comparatively small V12 spins quickly through its mid range, the torque pushing me firmly back on to the straight and the upper-end horsepower taking over with a sharp-edged yowl to blast me down the road.

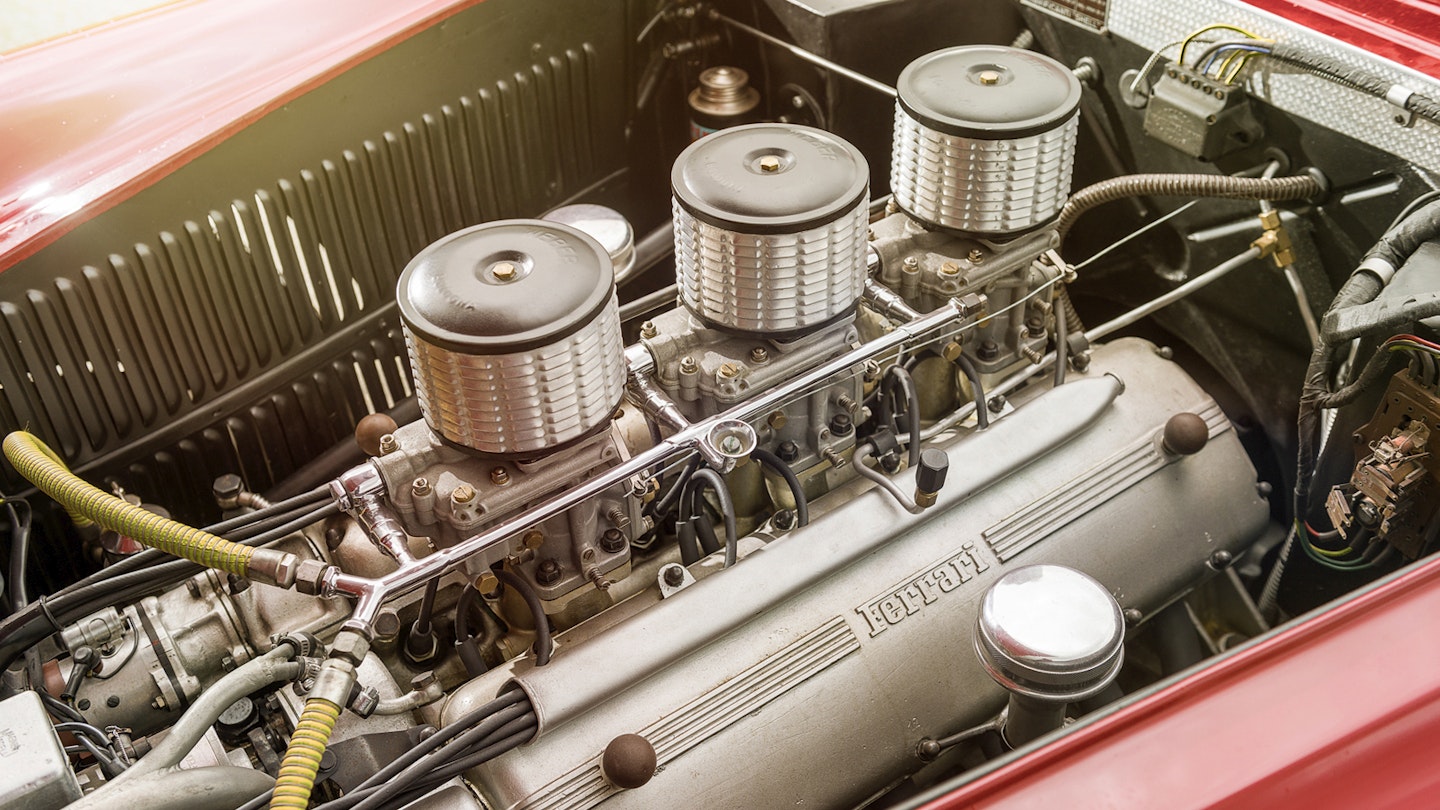

The motor is essentially the same as that of the 166; Gioacchino Colombo’s 2.0-litre V12 bored out to 2563cc and, in its most potent racing form, breathing through three Weber 36DFC carburettors. Even for that, it feels lively. Ferrari authority and historian Marcel Massini has more to say on that. ‘In June 1952 0158 ED was returned to the factory where both drivetrain and suspension were upgraded,’ he explains. ‘It had lighter, higher compression pistons (up to 8.8:1 from 8.5:1), a redesigned fuel and water pump, larger air intake and exhaust valves. Also, the rear differential was replaced with that of the new 340 AM.’

Bordonaro was obviously pretty serious about performing in the Targa. All the same, he would have to contend with this (original) five-speed, synchromesh-is-for-sissies gearbox. Before attempting a set of serious bends or hill climbs, I really need to brush up my Fifties gearchange chops.

The ‘raaagh’ of the engine spinning up and the generous breadth of its power band has had me going for the up-shifts too quickly. A Caterham-style snap-back of the delicate chromed wand won’t bring much more than a disgruntled zing from the meshing cogs, but better to take a blink-of-an-eye pause or come fleetingly off the clutch before going through to the next gear, maybe with even the faintest blip of throttle in between. Of course, double de-clutching proper is de rigueur on the down-changes. The pedal spacing allows me to control both brake and throttle easily with my right foot, though my ankle can be awkwardly angled in this seating position. Coming into a bend firm on the brakes, it’s best to give the throttle a firm flick with the side of the foot, the tacho needle jumping to follow the snarling motor through the revs. Clutch down again, stick back, clutch up; now with the smoothness of a Mercedes auto.

One of the enchanting aspects of Fifties racers and especially the Italian cars is the blend of ferocity and delicacy that is needed to make the car go swiftly and smoothly. However, I realise that I haven’t been applying this philosophy to the handling – I’ve just been trying to drag the car round the bends with the steering wheel. Even in a modern Ferrari I wouldn’t do that.

The 212 is light and has a very short wheelbase, and the V12 also sits quite a long way back in the frame. It’s almost front-mid-engined. It displays the three classic handling characteristics of so many old sports cars; running wide with two much power early in the turn, sliding its tail with too much shove just before an apex, and the nose tucking in when lifting off mid-bend as the tail lightens and the front end digs in. But what makes the 212 such an effective competitor is the merge and flow of these attributes.

In trying to bully the steering, I’m suddenly reminded of a conversation I had with ex-Chinetti driver Allen Markelson when he described how, in that era, drivers ‘steered’ around corners more with the throttle and brakes than they did the steering wheel. If I was to have any feeling left in my arms at all by the end of the Targa or the Mille, I think now is the time to practise those moves.

I soon realise that when I’m tugging the steering wheel too much, I’m doing it wrong. Gradually I’m working more with my feet to move the car around; braking to load up the nose and turn in tighter, getting back on the power to push the tail very slightly sideways. These are all small attitude changes; there’s no point in slurring the car all over the road. There certainly wouldn’t be on the Sicilian race or the Mille Miglia where the kerb might be a concrete post, a house or a sheer drop to certain doom.

For the most part, everything is beautifully progressive in the 212. The front suspension is independent with a semi-elliptical leaf spring keeping things even from below, while the rear is old school (and getting older by ’52) live axle. Even so, there is great transparency to the machine’s intentions, and transitions are felt intimately through the chassis. The most problematic scenario is a quick successive left-right where the short wheelbase accentuates the weight change. It could have you swapping ends quickly. Still, I’m soon at ease with the machine and this would allow me to improvise where a compound radius might be beyond the gesticulations of a cosily squashed-in co-driver – just think of the oft-photographed blind left-hand hairpin in the village of Collesano.

Yes, I’m convinced. Driven with insight, sympathy and a bit of nerve, the 212 has the agility and the power to take on any switch-back, roller-coaster road race, while its looks have the guile to enchant the ladies in pearls and linen twin-sets leaning on the pit counters at Cerda. Watching overalled mechanics and managers in dog-tooth tweed jackets pushing machines up the long incline to the start line, Bordonaro must have been fairly confident of a good race. Like any road race of the time, the Targa Florio start line contained quite a menagerie; the voluptupously muscular Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 Competizione, the low-slung, wide-mouthed, Stanguellini 1100 Sports, a Fiat Siata 1400 sprint – easily mistaken for another elegant Vignale-bodied Ferrari coupé. The curvy Maserati A6 GCS; diminutive yet still intimidating.

In the event, the top three places were taken by the disarmingly pedestrian-looking (but highly capable) Lancia Aurelia B20. Bordonaro and 0158 ED came a very creditable tenth. The pair would continue a very respectable, largely hill-climbing career before the nobleman sold the car to Swiss Eduard Margairez in July 1955. Margairez it seems was largely a circuit racer with a good few hill climbs thrown in. In April 1956 he took on Italy’s biggest challenge; the Mille Miglia.

By 1956, the 212 was outclassed in many areas although it was still a tough competitor in the right hands. Stirling Moss and Mercedes-Benz had torn up the track and record book in ’55 and the three-pointed star was back with more Gullwing 300 SLs. Ferrari had some svelte and potent sports racers prowling Brescia’s Piazza della Vittoria; the 300bhp 290MM. There were 750 Monzas and a host of Porsches driven by privateers.

The little 212 might fight with the best of them on the high passes, but on the long dash across the Lombardy plains the big bores would seize the day. In the deluge that befell the ’56 Mille, half of the 365 starters, including 0158 ED were washed out of the race. Eugenio Castellotti in a 290MM won.

If I were sitting in this 212 in the queue for the start ramp on the Mille Miglia, maybe watching Castellotti or Fangio’s big red road racer climbing the slope, or glancing at the Porsche Speedsters, OSCAs and Maseratis, would I rather be in one of them?

They’re all special – of course – but I’d be happy to do that race, or any other, in this. This was a model that helped forge Ferrari’s formidable reputation – slugging it out in desert dust, driving rain and on cobbled stone village roads. This example is a car that was in the centre of that contest, not merely some also-ran namesake bought from the show stand. I’d be happy to race this car because it has done all those things and could do them all again. If one phrase sums up any Ferrari 212 Export it would be, ‘bring it on’.