This Mercedes-Benz C111 is the only example with a V8 engine. Newly restored, we drive it in Stuttgart and learn how tantalisingly close the model came to production

The workman digging up the U-bahn platform on Stuttgart’s Heilbronner Strasse can scarcely believe his eyes. He jams his shovel into the rubble, pushes the peak of his hard hat up from his brow and gazes longingly at the metallic orange car burbling past him up the hill towards Killesberg. He’s suddenly come face-to-gullwing-door with a childhood vision of the future. Cogs spin in his brain as he searches back 40 years for a name. When he’s remembered it, he points wildly, waving his workmates over and shouting, ‘Es ist dass Mercedes – es ist der C111!’

I’ve never felt so self-conscious driving a car. This C111 – the sole remaining example of the 12 cars built to sport a reciprocating piston engine – is probably the only Seventies concept car in the world that gets recognised by passers-by in the street. There’s a good reason for that – if economic circumstances had been different in the early Seventies it wouldn’t have remained a concept. Car magazines, newspapers and investors begged Mercedes to put it into production and would-be buyers even sent the company blank cheques.

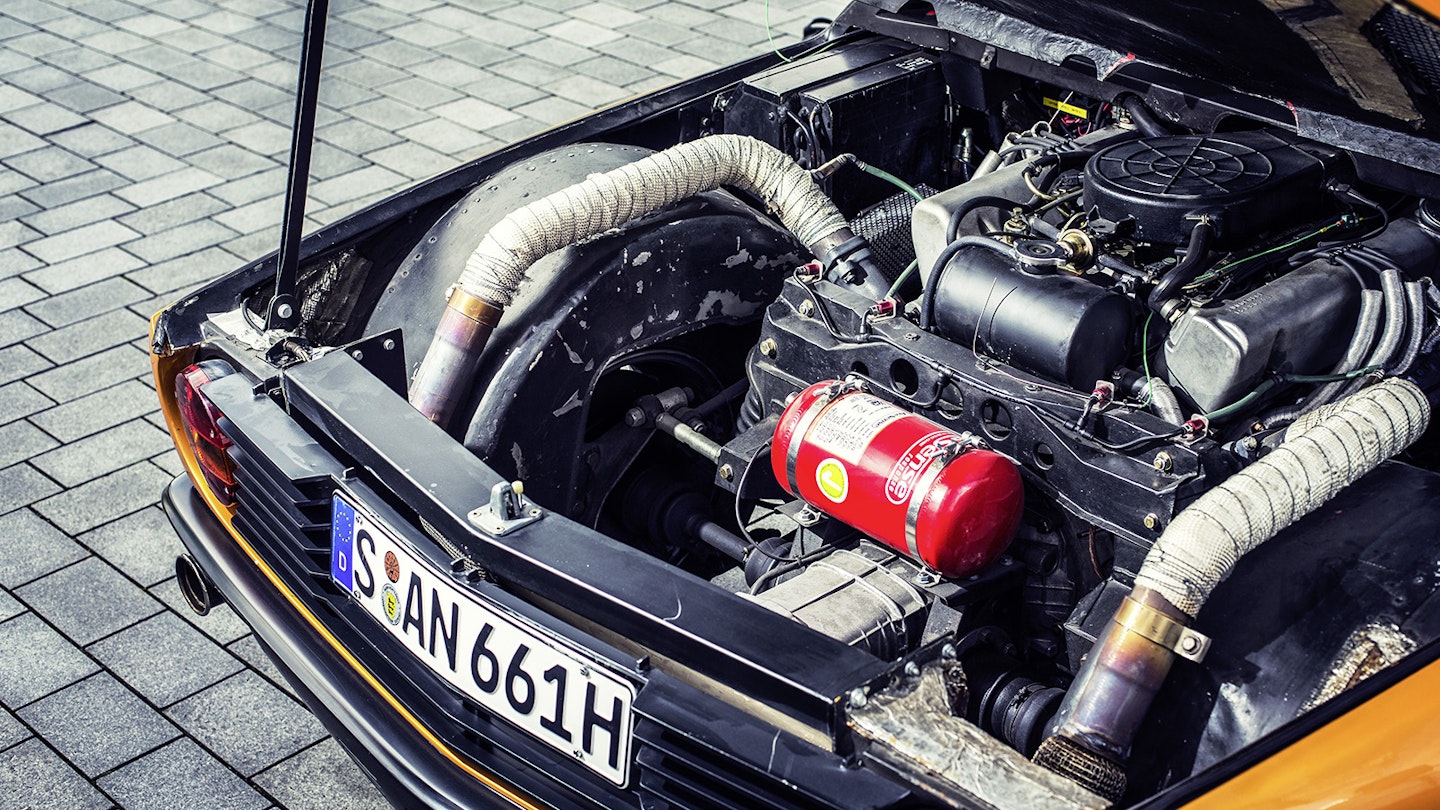

In 1969 Mercedes had intended the C111 project to be a test-bed for a new rotary engine, but quickly ran into the same rotor-tip reliability issues with its Wankel unit as NSU had. In 1970, without announcing anything to the public, Mercedes refitted two of its rotary concepts with 200bhp ‘M116’ 3.5-litre V8s from the then-new R107 SL. The reasoning was clear – if the troublesome 280bhp Wankel couldn’t be made to work, could the C111 make it to production with more conventional propulsion?

There are none of the usual concept-car bodges in this example; no dummy switches or non-functioning dials. The only aspects that feel unfinished, oddly enough, are the doors. They don’t rise to the same heights when opened, the handles feel flimsy and need manhandling into position before I pull them closed. There are no rattles from the dashboard and the switchgear all clacks firmly into action. As far as Mercedes was concerned it’s all rough-hewn and temporary, but had TVR built this car we would have been hailing a build-quality revolution at Blackpool. Either way, it’s further evidence that this car was not far off production-ready.

Entry is awkward because of a combination of high, wide sills and a massive steering wheel pilfered from an R107 SL, but once I’m settled into the tough tweed seat it’s comfortable in here – far more ergonomically successful than comparably flamboyant mid-engined contemporaries from Italian design houses, in fact.

The V8 grumbles behind my right ear at idle, suggesting an undramatic well of torque to draw on rather than a cammy, high-rpm opera. This sense continues as I slip the smooth-throw ZF gearbox into first and pull away. At low speeds it feels as though the car is being steadily muscled along by a rugby scrum. First gear is easily missed – sometimes I even have to press the reverse-lockout button to find it on its dog-leg – and occasionally I accidentally pull away in third. The C111 shrugs nonchalantly and purrs off the line. This is clearly an engine designed with torque-converter automatics in mind. It will happily cruise at 50mph in third without sounding flustered. Fifth gear seems almost superfluous.

But that ZF 5DS 25 transaxle gearbox is a very un-Mercedes item shared with classic supercars including the Ford GT40, De Tomaso Pantera and Maserati Bora. It can withstand 24 hours of race-winning abuse at Le Mans and is designed to unlock the potential of big, torque-laden V8s. At 3.5 litres the Mercedes V8 is far less muscular than these heavy-hitting opponents, but its 200bhp and sports-racer layout makes it directly comparable to another ZF-boxed junior supercar of the Seventies, the Maserati Merak SS.

Can a German car drive like a Maserati? South-east of Stuttgart lies the wine region of Untertürkheim, where the roads look decidedly Italian, undulating between hillsides serrated with vineyards. Traffic has dissipated, so I stretch the C111’s gear ratios. Propelling a lightweight glassfibre-bodied sports car, hooked up to this rather exotic gearbox, the M116 V8 reveals an aggressive side completely lost within the heavyweight automatic 350 SLs.

This C111 feels better built and more resolved than Berlinetta Boxers did as production cars

Low in its rev range, it feels relentlessly urgent, the torque surge accompanied by a thuggish boom echoing around the cockpit. Mercedes never tested it against a stopwatch, but I suspect its 0-60mph time easily outpaces the Merak SS’s 7.7 seconds. Beyond 4000rpm the bass rumble leaps upwards several octaves. Overlaid with gear whine, it’s a solid, meaty howl, higher in pitch than an American small-block due to its relative lack of cubic inches, but it avoids the brittle, trembling, seconds-from-destruction tremolo you hear in Italian supercars. It’s the sound of a particularly German type of engine, of Stateside-export dependability with Europe-friendly dimensions subjected to a Mediterranean thrashing.

Roadholding is reassuringly secure but the ride is rather odd. Mercedes wanted to move on from swing-arms at the rear and looked into using unequal-length double wishbones, but rejected them on the grounds of poor ride quality. I’m very glad it did, because the driver’s seat has only token padding between my back and its hard plastic shell. All the spine-friendly give is engineered into the suspension – conventional MacPherson struts and anti-roll bar at the front, with bizarre solid tri-axial hubs at the rear supported by three lateral links plus a pair of narrow trailing arms stabilised by hefty, diagonally mounted coil-over-damper units at the rear. As a result, while the front suspension squeaks and patters, the rear lopes and bounces softly. It’s a great compromise for a car like this, especially in a mass market, but I couldn’t see Ferrari opting for it on the 512BB.

Unfortunately, Mercedes raided its parts-bin for the recirculating-ball steering. A car like this should ideally have a rack-and-pinion set-up, allowing a slight nervousness from the helm that can be exploited and turned into sudden, intuitive reactions. Instead there’s a dull vagueness that’s so soft it feels power-assisted except at parking speeds, when I find myself hauling heavily on the huge steering wheel. It’s acceptable at three turns lock-to-lock, but it’s not what anyone would call sporty.

Turn in hard and the body creaks as the weight lurches diagonally across the chassis, leaning hard on the outer 195/50 VR14 front tyre. At A-road speeds the C111 tracks neatly through the bends, but I can’t avoid thinking that the weight transfer might be enough to upset the roadholding at higher velocities, with a sudden mid-corner throttle lift or sharp braking into a turn translating into snap oversteer. Still, comparable driving characteristics didn’t stop sales of the Porsche 911, another car the C111 would have found itself rivalling had it made it into production.

The suspension set-up on this C111 may seem snappy, but it was engineered to avoid the squat and dive that had plagued swing-axle Mercs since the Forties. By the time C111 development had reached its limits in 1979, the cars had helped Mercedes create anti-lock braking systems, higher-speed-rated tyres, powerful turbodiesel engines and the patented multi-link rear suspension system – which can all be found on every range of today’s Mercedes cars.

Because of this it’s easier to forgive the C111’s minor handling shortcomings. This isn’t a set-up intended to be user-friendly, but to test the adhesion of tyres, movement of suspension and strength of brakes – and be incrementally adjusted by engineers. Lift up its rear clamshell, gaze at the elegant spaceframe chassis, and it’s obvious this car could have outhandled such set-up-sensitive opposition as the De Tomaso Pantera had it been destined for the mass market.

A now-redundant button on the dashboard hints at the life this C111 once lived. It’s marked ‘ABS’ and once activated an anti-lock system, long since removed. Once Mercedes had decided not to put the C111 into production, the cars’ tendency to punish brakes and tyres made them ideal mules for development work. C111s were responsible for helping the firm banish its reputation for making ponderous, wayward cars for an ageing establishment class and access more youthful buyers.

As I cruise up the A10 back to the C111’s home I can’t help but feel a sense of retrospective frustration with the Mercedes management’s conservatism in the Seventies. Set among the context of this car’s Italian contemporaries, the C111 feels better-built and more resolved even in concept form than the Modenese did as production cars, and yet Ferrari had no problem selling more than 2000 high-maintenance Berlinetta Boxers. Mercedes may have had hang-ups about building a glassfibre car but, awkward door latches aside, it feels several generations ahead of a comparable Lotus Esprit. The V8 engine is reliably fuel-injected, not fed by a multitude of hard-to-balance carburettors. The gearbox doesn’t need warming through before first is engaged. Whichever way I look at it, I just know that the people who bought supercars in the Seventies would have found this C111’s finish and execution perfectly acceptable.

The C111 settles to a gentle cruise on the autobahn and I switch on the Becker Grand Prix radio, finding a typical German drivetime rock radio station still wallowing in reunification-era nostalgia. As the cockpit swims in the synth-heavy chords of Blue Öyster Cult’s Shooting Shark (as clear as any modern car stereo thanks to an impressive lack of wind noise) I realise that it sounds appropriate. This supposedly shonky handbuilt C111 feels more like a product of the late Eighties than one killed off by the 1973 oil crisis.

And it’s this aspect that makes Mercedes’ decision not to build the C111 seem so cruel. Given enough time in production – longer than the doomed BMW M1, at any rate – it could have become a supercar icon to generations of German teenagers. Although it emerged on the future-shock design-expo scene of the late Sixties, the C111 wouldn’t look out of place in soft focus among dry ice and baying guitars 20 years later. It’s only dated by very minor, easily updated details, putting it in the same milieu as other long-lived futurists such as the Porsche 928 and Lamborghini Countach.

Mercedes could have added more power too, to keep it competitive. Although the idea of a V8 C111 was curtailed (at least in part) because 200bhp was deemed uncompetitive and the 3.5-litre M116 small-block was such a tight fit, the M116’s capacity was eventually expanded to 4.2 litres, yielding 231bhp at a 9.0:1 compression ratio for the blousy 420 SL. It doesn’t take much imagination to wonder what more could have been extracted with higher compression and forced induction, especially given the activities of German Mercedes tuners such as Lorinser, AMG and SGS in the Eighties. Even in standard tune a 4.2-litre C111 would no doubt have kept pace with a Ferrari 308 GTB Quattrovalvole.

In the end it was left to B+B Design’s Eberhard Schulz to bring the idea of a Mercedes-powered supercar to market. But his Isdera 033 was a pastiche built by a Ford GT40 kit car manufacturer at a rate of three per year. Had Mercedes shown Schulz’s determination, put aside concerns about the oil crisis, shown faith in the V8 and made a stand against the Italians, the C111’s successors could be gracing teenagers’ bedroom walls to this day.