[ TVR T350c prototype ]

This prototype T350c embodied everything TVR would have been in the 21st Century. Was it a wrong turn or a last gasp of greatness?

Words SAM DAWSON Photography IAN SKELTON

I have to keep telling myself that this is a prototype. It may look like any other TVR T350c at first – the car which the Blackpudlian firm saw as its new mainstream offering in 2002, a step up from an MX-5 or an alternative to a Z4 – but user friendly, it isn’t. Just to fire the ignition, you have to turn the key one click in the barrel and press a button on the fob, then press two unheralded triggers on the back of the steering wheel – twice – to activate the fuel pumps. Only then can you turn the key a second click and the engine will finally start.

And far from the silken, carefully-tuned snarl you’d get from its Bavarian rival, there’s a deep, pebbledashed grumble. Thanks to these Speed Six TVRs’ dry-sump oil systems, they need thoroughly warming through before you dare – or are permitted – to indulge the throttle. Until then, they sound both cantankerous and unhealthy.

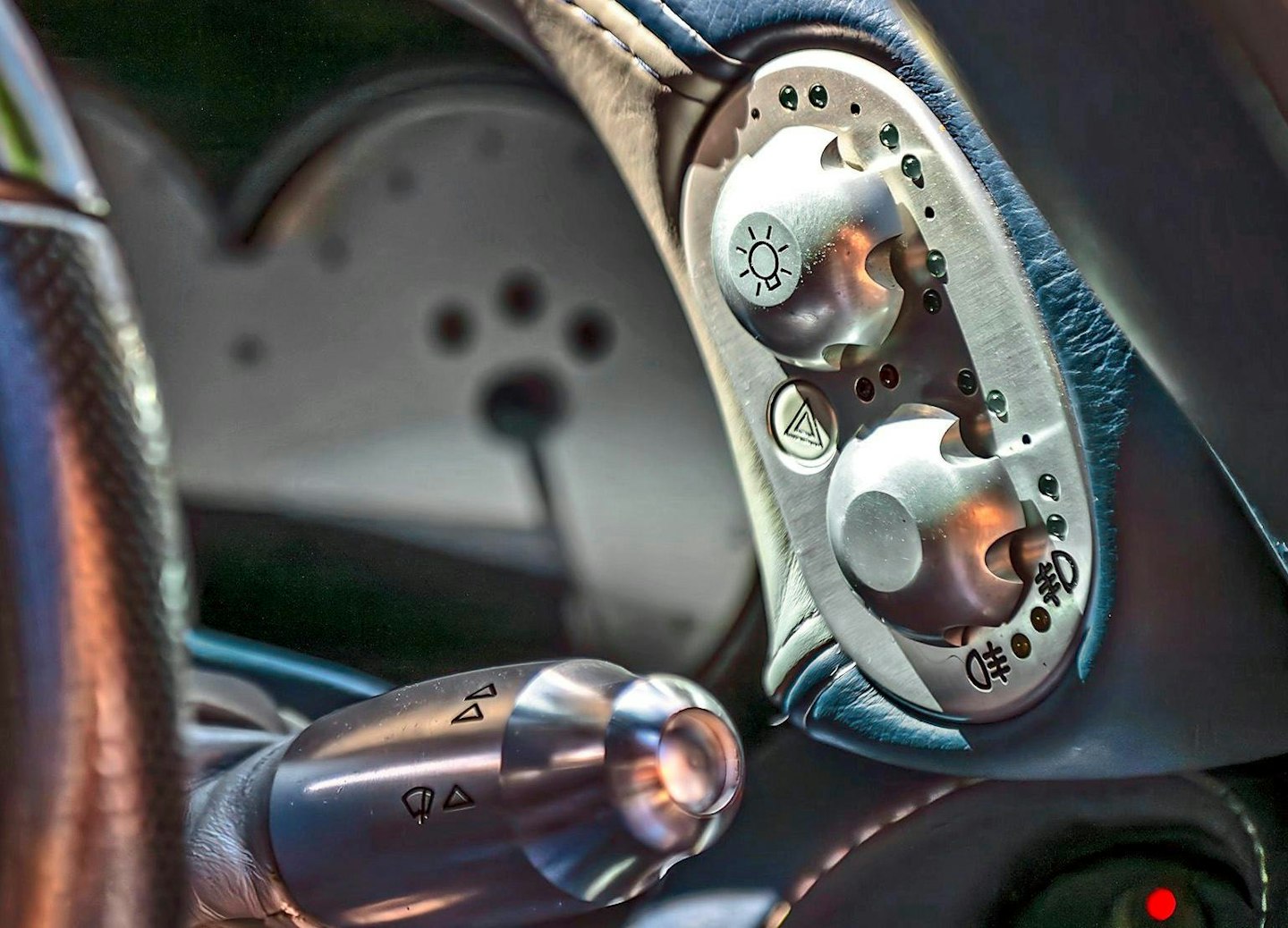

The cockpit is cramped and tight too, with a beetle-browed view out of a windscreen so low and slit-like that TVR didn’t even bother with sunvisors. It’s beautifully trimmed, in quilted leather with bespoke aluminium fixtures everywhere you look, but in time-honoured TVR fashion it still contrives to smell predominantly of hot oil and glue. And of course, the dashboard is borderline incomprehensible, a combination of unlabelled switchgear, LCD screens ablur with constantly-shifting numerical readouts, and a metallic speedometer and tachometer with not enough visual contrast between needles and instrument faces, not enough numbers round the perimeter, and an odd, digitally-controlled jerky action that makes it difficult to gauge the progression of anything. The only message I get from it is, ‘keep your eyes on the road’.

Sharp-cut tail for enhanced aerodynamics Unmistakably TVR, intensely focused

But as I have to keep remembering, this is a prototype. It may well have been rushed to completion too. Before the launch, in its last pre-Clarkson-reboot twitchings, Top Gear sent Jason Barlow to Bristol Avenue to check on the progress of a new generation of all-bespoke TVRs due for arrival at the 2002 British Motor Show at the NEC in Birmingham. TVR PR man Ben Samuelson confirmed that the new T350 range had been turned around in just six months, although ahead of the show admitted the development crew was ‘getting twitchy’ as the deadline loomed. Even boss Peter Wheeler knew it wouldn’t be completely finished by the time the car arrived at the NEC. At 10pm the night before opening press day, it was still being trimmed. To this day, neither the door mirror adjusters nor the heated rear window elements are wired up.

The following morning, Samuelson pulled the covers from this very T350c in front of a frenzied barrage of press flashbulbs, while Wheeler drove up onto the stage in a second prototype finished in metallic green. The price for this new TVR, Samuelson said, would be just £37,750.

TVR, so it seemed, had done the impossible yet again. Ever since Wheeler replaced Martin Lilley at Blackpool in 1981, his genius combination of relative mechanical simplicity compared to mainstream rivals, huge power and thorough chassis engineering had carved out a unique niche. Old-fashioned tubular-backbone chassis construction also meant it was possible to essentially rebody the same underpinnings with minor variations to create ‘new’ models far faster than ponderous industrial-giant companies could comprehend. The result was an ability to profitably sell cars at prices seemingly completely out of whack with the amount of performance on offer. The T350c had 290bhp, did 0-60mph in 4.4 seconds, and topped out at 175mph. That left the similarly-priced top-end BMW Z4 3.0 a long way behind. Against the clock, the TVR matched the £103,000 Ferrari 360 Modena.

Direct steering makes T350c an extension of driver

Designed by engineers, not accountants

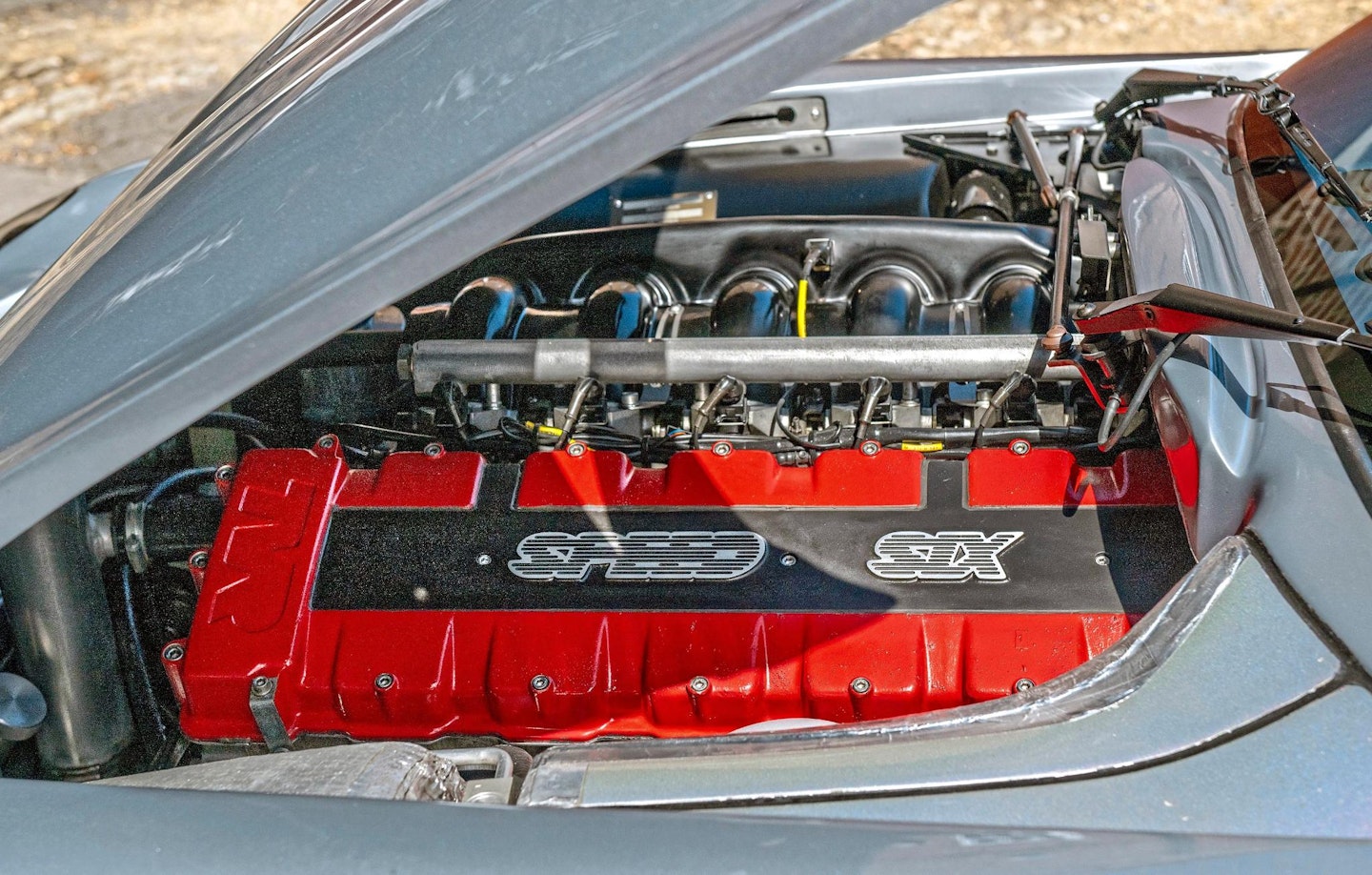

In truth, as journalist Harry Metcalfe suspected when he road-tested this car after the show, the prototypes were even faster, hinting at what was to come. It has a 4.0-, rather than a 3.6-litre

Speed Six, in the manner of the yet-to-be-announced, racing-inspired Sagaris. In other words, 400bhp, just four seconds to 60mph, and a top speed quite possibly higher than 190mph, given this prototype’s lack of the Sagaris’s downforce- and drag-inducing splitter and gurney flap. Forget the 360, this is 575M Maranello territory. In something the size of an MGB.

Perhaps the biggest surprise this T350c springs, given its almighty performance potential, is how compliant it seems. There’s something about the immediacy of its steering, with its 1.8 turns lock-to-lock, that makes it feel like an extension of my own body on this twisting country lane south of Oxford. Thanks to their separate-chassis construction, convertible TVRs never suffered from scuttle-shake anyway, but the T350c’s hard-topped structure feels impressively stiff, a sense heightened yet further by Wheeler’s decision to plumb a roll-cage into the cockpit to quickly evaluate the car’s suitability for GT racing.

Sumptuous trim doesn’t scream ‘prototype’

Gearbox one of many sensory experiences

And yet the chassis breathes with the road in that time-honoured British front-engined sports-car fashion. This was a product of the early 2000s, a time when it seemed that a car’s perceived ‘sportiness’ could be measured in a near-complete lack of suspension travel and a harsh, buzzy cockpit full of Alcantara. Yet there’s an old-fashioned nuance about the way the T350c reads the road beneath it, with long-travel dampers, that’s more reminiscent of a Jaguar E-type or Lotus Elan.

It might have been TVR’s platform for the future but there is something satisfyingly timeless about the way the T350c looks too. That sleek, low nose was shaped to lower wind noise according to Samuelson, but curves are paired with a Manx-tailed abruptness that instantly recalls the Grantura. The boomerang light clusters and drilled undertray may look radical and futuristic, but that glass rear hatch is pure Taimar.

Even lightweight detailing is beautifully done

Pipe dream: production T350c made 350bhp; prototype, 50bhp more

I find another link to the past when I take my left hand off the wheel and reach for the gear lever. The steering is so direct that even doing this is enough to make the nose twitch. Then go for the gearshift: short and stubby, sitting high on a quilted leather-clad transmission tunnel, the aluminium ball scalding in the summer heat. Flick it across the gate with a firm sense of purpose, feeling steel linkages yank cogs back and forth below. At a time when cars with this kind of performance were being increasingly offered with soulless done-for-you sequential transmissions, it’s another sensory cue that links this post-Millennial car to 50 years of predecessors.

But with oil flowing freely through its arteries, that Speed Six engine is savage. Rather than the rumbling off-beat of the TVR-tuned Rover V8s in Wheeler’s earlier cars, at half-throttle there’s a rapid, precise metallic clatter, like a Victorian mill full of looms. Press the pedal harder and it coalesces into a powertool shriek, intensity building in parallel with road speed and revs. No, a Porsche might not feel this phrenetic, but you’d have to go back to the days of the aircooled 911 2.7RS to find one that felt quite so viscerally alive. The brakes may lack ABS, but rather than feeling like an example of Wheeler’s behind-the-scenes cost-cutting, it smacks more of racing practice. They haul the T350c up firmly and decisively, so long as you’re progressive and nuanced with your right foot. Stamp on it, especially in the wet, and it’ll no doubt both lock and slide.

TVR really had a handle on bespoke parts

Details point to a far from regular T350c

But as was always thus with TVR – they’ll only bite if you’re foolish with them. The problem TVR faced when it launched this T350c was that attitudes were changing. The 2001 action blockbuster Swordfish had handed a starring role to a TVR Tuscan alongside John Travolta, resulting in a clamour from Americans to buy them, despite the fact that the cars’ lack of ABS and airbags rendered them ineligible for sale in the US. The Speed Six engine wouldn’t meet US emissions regulations either.

The impetus, however, was there for the first Federalised TVRs since the early-Eighties Tasmin, but it would need an off-the-shelf engine from a third-party supplier in order to make economic sense. And not just in the US either. The likes of the Porsche Boxster S and Mercedes-Benz SLK32 AMG might not have been quite so quick as a TVR in terms of raw figures, but they came from mainstream dealerships, had comprehensive warranties, could be sold all over the world, and were so reliable that they could be used every day in all weathers.

Since BMW bought Rover in 1994, Wheeler had known that its V8, which had powered TVRs since 1983, wouldn’t be long for this world. But with the Nineties sports car boom mutating into a new breed of big-brand affordable junior supercars, the question of where to source a replacement engine was vexed, especially in a world where transverse installations and front-drive was the mainstream norm. Of the remaining rear-drivers, the likes of BMW and Mercedes built their own TVR rivals and wouldn’t countenance the idea. Toyota was about to discontinue its Supra, Nissan’s 350Z launch was imminent, and any American V8 would put TVR in direct competition with the dynamic-handling – and £10k cheaper – Chevrolet Corvette C6.

‘I find myself homing in on the very kinds of detail that made the accountants so irritable’

TVR persisted with its Al Melling-designed dual-purpose road-and-race AJPV8 and Speed Six engines, but even by the time the covers were whipped off this T350c in Birmingham in 2002, the firm was in trouble. After a late-Nineties heyday selling well over 1000 cars a year, peaking at 1676 in 1998, the main bulk of which were Rover-powered Chimaeras, sales had gone into freefall. Just 978 cars were sold in 2000 as the Speed Six debuted in the new Tuscan, a promising 550 being shifted in its first year, but as warranty claims started racking up regarding the new engine’s brittle camshaft finger-followers, and drivers used to more mainstream sports cars found themselves infuriated with its idiosyncratic electrics, sales fell dramatically. By 2001 TVR sales were down to 667, 632 in 2002, and the new T350c seemingly did nothing to reverse the decline. Despite it being TVR’s biggest seller of 2003, with 231 finding homes, it compared poorly as a range mainstay to the Chimaera, of which 1115 had been sold in 1998, just five years earlier.

In 2004, on the quiet, Peter Wheeler put TVR up for sale, having not publicly released any company finance details since the T350c’s 2002 reveal, which had shown the company to have made a £400,000 profit that year. CAR magazine called upon independent automotive-industry business analyst Garel Rhys to make sense of the situation, and he postulated that TVR was indeed in an impossible situation: its own engines were too unreliable, anyone with a viable off-the-shelf powerplant already made its own TVR rival, and to make matters worse, TVR’s insistence on doing everything in-house in the name of maintaining independent control and bespoke design, right down to the interior switchgear, had made developing the cars unfeasibly expensive. It was very much a firm, Rhys reasoned, where the engineers had elbowed the accountants out of any positions of decision-making authority.

T350C blends Ferrari 575M Maranello power with MGB footprint

‘Once oil is flowing freely through its arteries, the Speed Six engine is savage’

And yet, as I pull up in the village of Dorchester, I find myself homing in on the very kinds of detail that made those accountants so irritable. There is only one external handle, and it’s a beautifully-turned aluminium talon of a thing mounted at the base of the frameless glass tailgate: unique, as production items were redesigned when Wheeler found it trapped his fingers when closing the boot. There’s a dimple in the bodywork after the fuel filler was re-sited – Wheeler found the original difficult to open, and despite being a laborious process – you have to open a little upholstered door in the boot and pull a hidden lever – it’s just so elegant, a hemisphere of aluminium rolling back to reveal the filler neck. And of course the doors, opened not by conventional handles, but by buttons underneath the mirrors, leaving the flanks completely unadorned. Wheeler always claimed they were an ingenious anti-theft measure, but all of these elements are examples of what nauseating mainstream car marketing types refer to as ‘surprise and delight features’. Little pieces of theatre typically used to add pizzaz to some unremarkable runaround. But on a TVR – just about as theatrical as cars get this side of Sant’Agata regardless of how you get the driver’s door open – they seem like evidence of something else. Was Wheeler really safeguarding his supply chains, or just wanting to go out in a blaze of bespoke glory?

Six-cylinder engine 4.0-litre unit, not production car 3.6

This car’s life hints at the turbulence that beset TVR in the early 2000s. After doing the motor show rounds, it was resprayed in the conventional metallic silver you see here. Originally it was Spectraflair Pebble Lamonta, which blended blue, silver and gold depending on how the light fell on it. But after six months of being subjected to track testing by TVR engineers and motoring journalists alike, it was peppered with stonechips. Lift up the bonnet, though, and you can still find some Spectraflair luminescence lurking in its slam panels.

But after that early buzz of activity, having covered 30,514 test and development miles, it languished. Russian entrepreneur Nikolai Smolensky bought TVR in July 2004, and announced that all future models would be on limitedproduction runs of 500, seemingly to duck under the numbers that would incur the requirement for increasing numbers of mandatory safety systems like ABS, traction control and airbags. Despite this, Smolensky saw the dramatic Sagaris through to production in 2005, but all was not well. Production dropped to just three cars a week. In October 2006, Smolensky announced that TVR production would be transferred to Turin for 2007, claiming to have reached a deal with Bertone, although the carrozzeria refuted it when questioned by Automotive Management magazine. Curiously, three weeks later, this prototype was back on the road, receiving its first MoT certificate on 6 November 2006 before being sold to TVR dealer James Agger. Smolensky had just made 250 staff at the Bristol Avenue factory redundant.

How could a car that looks like this sell poorly?

‘Whether this car marks the beginning of the end for TVR depends on your perspective’

Whether this car marks the beginning of the end for TVR, or is an embodiment of a series of missed opportunities and cruel twists of fate which ultimately silenced the thunder from Blackpool, depends on your perspective. There’s no denying its wilfully user-unfriendly quirks, but in reality these had been a growing theme on TVRs since the Cerbera of 1993. But it does seem to mark a fulcrum point in the existence of the firm. From this car, and this prototype’s ballistic four-litre engine, we got the firm’s true defiant final act in the form of the Sagaris. And yet, it also embodies the moment when TVR turned its back on the mass-market recipe that had introduced TVR to so many new customers via its predecessor Chimaera.

But it also marks the very last of a single-minded breed of British sports car, before legislation effectively banned it. Intense, uncompromising, focused and gloriously mechanical, it’s the first of the last of its kind.

2002 TVR T350c prototype

Engine 3996cc in-line six-cylinder, dohc, TVR electronic fuel injection

Power and torque 406bhp @ 7000rpm; 349lb ft @ 5000rpm

Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack-and-pinion

Suspension Front and rear: independent, double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes Front and rear: vented discs

Performance Top speed: 190mph; 0-60mph: 4sec (estimated based on Sagaris)

Weight 1187kg

Fuel consumption 22mpg

Cost new £37,750 (standard production T350c)

Classic Cars Price Guide £16,500-£27,500 (standard production T350c)

OWNING A TVR T350C

‘I’d had a Triumph GT6, a Porsche 996 and a Turbo Technics Ford Capri, but I’d always wanted a TVR,’ says owner Jonathan Hampton. ‘I didn’t care about the reputation for unreliability, I wanted something to drive, so I swapped the Capri for a Griffith and never looked back.

‘I saw this T350c at a dealer a few years ago, but before I had the chance to see it, it went up for sale at Iconic Auctioneers. But it didn’t sell, so I tracked down its original dealer, James Agger, he knew the guy who was selling it, and he put us in touch.

‘Since then, it’s been perfectly reliable. I’ve driven it to France and it never missed a beat, although it was completely restored by TVR specialist Str8Six in 2009 – it was there where the engine was discovered to have been a 4.0 rather than a 3.6, and essentially the same specification as the Sagaris. They also found that Peter Wheeler had signed the inside of one of the doors.’

Subscribe to Classic Cars today. Choose a Print+ Subscription and you'll get instant digital access and so much more. PLUS FREE UK delivery.